On the day I was born—on October 5th, 1949, in Saint Anthony Hospital, Oklahoma City—I nearly died.

The story is that I had trouble taking and holding a breath. My mother, always ready to inject exaggerated drama into her stories, told me that in order to breathe, for the first week of my life, I had to be passed from nurse to nurse and spanked. She also told me that she promised that if God kept me alive, she would dedicate my life to God’s work.

It does something to a person to be told something like that.

Both of my parents were native Oklahomans: my father from rural, eastern Oklahoma, my mother from urban Oklahoma City. They were both children of Great Depression poverty, both children of single mothers. I grew up acutely aware of the fact that my parents had very hard childhoods and that I didn’t, “only child” that I was.

I am of mixed heritage. When I was not quite 8-years-old, in 1957, we packed up and moved to Chicago, where we lived for the next five years. Going north was a career move for my dad. It was good for us to make that move, but my parents never stopped longing to go “home.” I was raised to long to go “home.”

I grew up in the American Midwest and Southwest. My high school years were spent in Hobbs in southeast New Mexico, a little oil town barely west of the Texas state line. HHS was my ninth school.

As I approached high school graduation, my pastor talked me into attending Bethany Nazarene College (now Southern Nazarene University). Bethany is a suburb of Oklahoma City. And so, at last I’d returned to the land of my birth, the land of my (recent) ancestors!

I joined the Church of the Nazarene in Hobbs, but I had attended churches of that tribe, since we lived in Chicago. I was ordained (as a “deacon,” a second class ordination distinguished from “elders orders” only by the latter’s enclosure within the category “preaching”) in the mid-1990s, after some pretty serious and humbling self-examination. (This is not the place to explain this, but, as was the case also in our marriage, I came to the point where it was not enough—to paraphrase and flip Dylan—to give it my heart. It was time, past time, to give it my soul, as well.)

I was (first “assistant,” then “associate,” and then “full”) professor in four universities. The first three were institutions of the Church of the Nazarene (Point Loma, Trevecca, and Olivet). The fourth was the vaguely Wesleyan (but mostly entrepreneurially “evangelical”) Azusa Pacific University. All these universities were self-consciously evangelical. I wasn’t. It’s not that I was “progressive” or even “moderate” (I like to think of myself as a “digressive”). I was mostly just confused and wrestling overtime with the subject matter of theology, in order to stay alive. Theology has been the chief means of grace in my life, whatever else it might have appeared I was doing. Most of my teaching roughly the first fourteen years of my “career” was in philosophy. Philosophy was my Leah. Then I became a full-time professor of theology, my Rachel, in 1994.

I think I've always been an indirect theologian. I have certainly always from my earliest childhood been a big fan of popular culture, especially music, film, and (this may seem out of place, but I think it isn't) standup. I would spend hours trying to understand, e.g., Bob Dylan songs. I also read the Bible from a very early age as a mysterious text with hidden meanings. And so, I was ready to think theologically not unlike the way one might think and perform art. So, when, from time to time, I say that I am a "nonlinear" systematic theologian, I'm thinking of the logics by which art "makes sense," especially performatively, the way, e.g., a punch line gathers the particulars of a string of straight lines and flips them. But I'm also thinking of the etymology of the word "system." A system in this sense may be as roomy as the notion "standing together." I'm certainly looking for roominess whenever I do theology.

Of theological thinkers, the ones who have most consistently contributed to the way I have come to think are Kierkegaard and Wesley: Kierkegaard, in part because of the way he self-consciously thinks in contrast to internally coherent, linear "systems"; Wesley, because, in spite of his desire to see everything fall neatly into place according to an Aristotelian balancing-of-the-books, he cannot make the work of the Spirit cooperate. But I was also early in my graduate studies deeply influenced by Luther and then, in the light of Luther, Barth. My Ph.D. dissertation is on Barth and Pannenberg (Dominus Deus Novus: An Experiment in the Transcendence of God from the Theologies of Karl Barth and Wolfhart Pannenberg), and so, Pannenberg also made a contribution to my way of thinking, both as a contrast to Barth (since Pannenberg is driven to have everything fall together under a fully comprehensive, historical "unity") and as a way of stressing the apocalyptic dimensions of Barth's work, especially an apocalyptic priority of the future. By thinking the future as the redemption of all that has been, it becomes possible to think the world (as it is and has been) as a chemical mixture awaiting an outside catalyst that will yield a congealing chemical reaction, one that could not happen without the catalyst, but also (and I think this is the Augustinian side of Pannenberg) as a text awaiting (as German sentences often do) a phrase at the end that will give the whole its sense, often changing what the reader was expecting. (I've actually preferred the metaphor of the punch line that gathers and flips the text, as I mentioned above.) Derrida has been very helpful in addressing these issues, too, as well as the whole apophatic tradition, especially of the East. Barth has his own variation on these themes. What I am doing is similar to Barth's rather Mozartian method of working out more and more widely looping variations on a theme, but I think there's more apophasis in my work, more effort in getting words and ideas off of themselves. Barth is, of course, all about getting words and ideas off of themselves, but there are way too many instances of his making short lists (generally numbering "3") of the aspects of some issue. The Dogmatics often gives the impression that Barth is sticking to a plan, even if he works overtime to undo any and all planning.

My inclination to a certain kind of politics (which I sometimes call “ecclesial anarchy”) has a lot to do with the fact that both of my parents were desperately poor during the Great Depression (and told me too many stories about their childhood, when I was growing up), and because I came of age during the social upheaval of the 60s. And so, I've spent a lot of time thinking about justice as something other than balance, thinking of it in fact as imbalance, really, as a preference for the poor. I was inclined in this direction long before I encountered liberation theology. I was drawn to Marx early on, too, but increasingly with my exposure to people like Gutierrez. My reading of Ted Runyon's introduction to the collection Sanctification and Liberation, in which he explicitly compares Wesley's relationship to the quietists with Marx's relationship to Feuerbach, was extremely helpful. My Luther-leaning protestantism made it very hard for me fully to embrace Wesley's emphasis on works prior to my reading of Runyon. Reading Wesley and Marx together has been very helpful. I now think of Wesley's stress on works as his stress on embodiment, that we are embodied and that bodies work. As for Marx's understanding of work (obviously a much more nuanced economic vision than anything in Wesley, who has his own kind of nuancing of the idea), I have been pretty heavily influenced by Richard Bernstein's analysis in the book Praxis and Action (an older book I'd still strongly recommend, if only because of the chapters on Hegel and Marx).

I am now “retired,” 69-years-old at this writing, still not having settled down, trying hard to learn how to be a husband again, to Elesha, who has saved my life more times than anybody has a right to expect even from a spouse. Next April (2020) we will have been married 50 years. Being married to Elesha has been hands down the hardest and best thing I’ve ever done (as if marriage were something anyone ever does). I practice the saxophone, if all goes well, every day. Elesha and our three kids—Heather, Stefen, and Bryan—gave me a 1954 Selmer Mark VI tenor (serial number 56,000+) as a retirement present. (It is an amazing horn.) I have yet to figure out how to read and write daily, but I’m getting close. We live in San Diego. If all goes according to plan, in a couple of months from now, all of our children and grandchildren will have come to reside in this fair city, as well. It’s a nice way to walk into the setting of the sun.

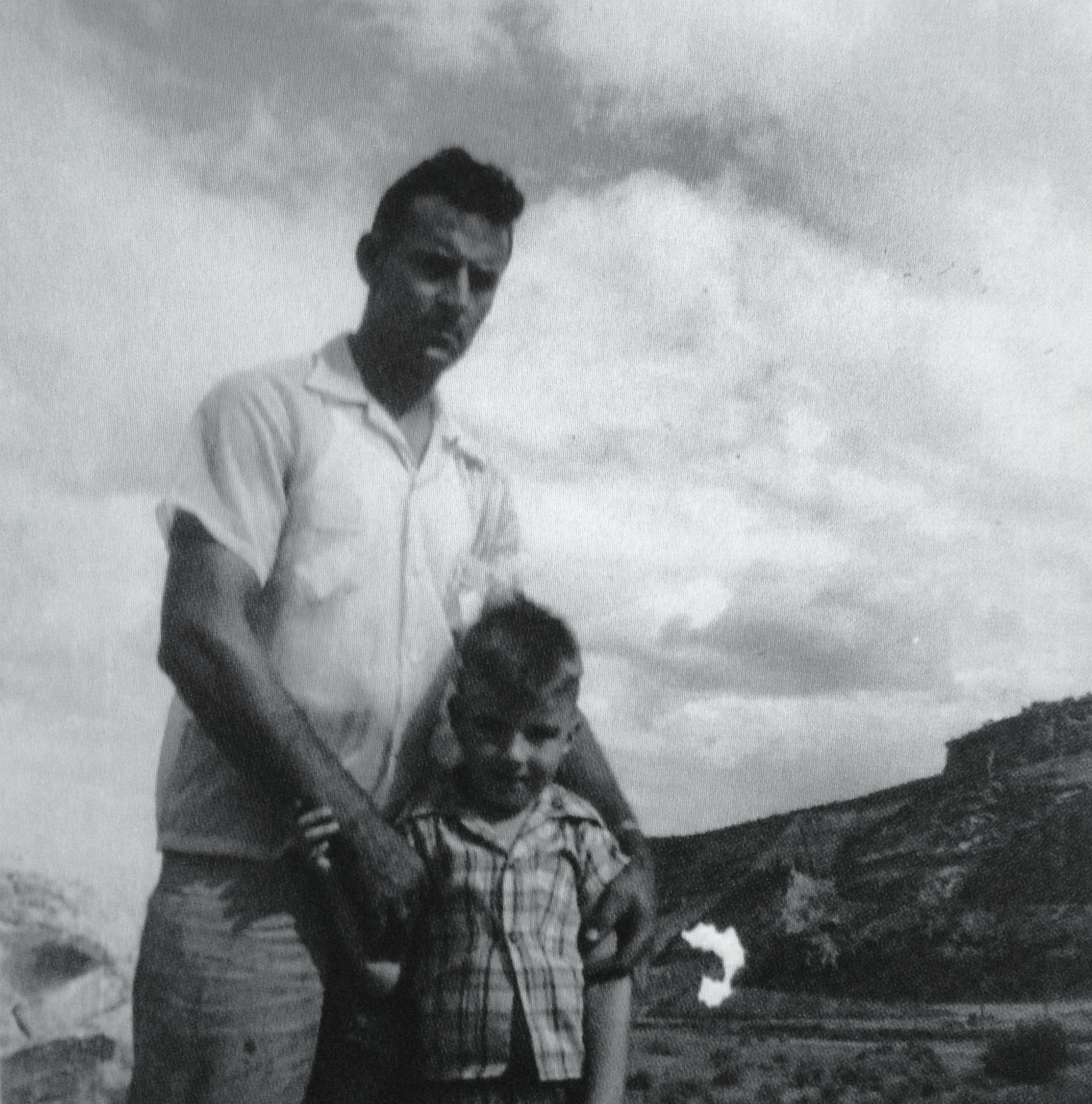

Our son Bryan is the editor of this blog. He has chosen (sometimes with my suggestions) the pictures that accompany my words. The one below is especially fitting. That’s my dad, James Walter Keen, looming over me, when I was very small and we were on one of our many vacations in Colorado. Old man that I am, I still feel that even now he is looming over me in that way. He never really understood what I was about, not when I was small and not when I was big. He did always love me, however. It was one of the great gifts of my life that I lived with him in our home the last three years of his life and that I was with him when he died. He was a tender soul with a very harsh and angry persona. Those last three years he turned into a gentle, kind, and grateful old man. Those years went far toward stitching up old wounds and reviving my affection for him, which still stands strong.

Occasional Thoughts:

Since retirement, I think I’d hoped to live a largely uninhibited life. My life, especially my adult life, was prior to retirement characterized (believe it or not) by a great deal of focused “self-control.” There are lots of reasons for that and I don’t doubt that inhibition is a normal mode of human life, especially in a culture domesticated by mass communication and a constant barrage of standardizing images. I now understand that it has not been helpful for me to experiment with dialing down my inhibitions. Among other things, it has led to a kind of “selfishness.” The “self” that has risen has not been Cartesian or the object of a kind of incurvatus in se. It has rather been the diffuse “self” of impulse. So, at any rate, this is a confession and apology for the last few years and a sort of pledge to be much more vigilant here on out.

Here is my prayer (first prayed by Hilary of Poitier):

I am well aware, almighty God and Father, that in my life I owe you a most particular duty. It is to make my every thought and word speak of you.

In fact, you have conferred on me this gift of speech, and it can yield no greater return than to be at your service. It is for making you known as Father, the Father of the only-begotten God, and preaching this to the world that knows you not and to the heretics who refuse to believe in you.

In this matter the declaration of my intention is only of limited value. For the rest, I need to pray for the gift of your help and your mercy. As we spread our sails of trusting faith and public avowal before you, fill them with the breath of your Spirit, to drive us on as we begin this course of proclaiming your truth. We have been promised, and he who made the promise is trustworthy: Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you.

Yes, in our poverty we will pray for our needs. We will study the sayings of your prophets and apostles with unflagging attention, and knock for admittance wherever the gift of understanding is safely kept. But yours it is, Lord, to grant our petitions, to be present when we seek you and to open when we knock.

There is an inertia in our nature that makes us dull; and in our attempt to penetrate your truth we are held within the bounds of ignorance by the weakness of our minds. Yet we do comprehend divine ideas by earnest attention to your teaching and by obedience to the faith which carries us beyond mere human apprehension.

So we trust in you to inspire the beginnings of this ambitious venture, to strengthen its progress, and to call us into a partnership in the spirit with the prophets and the apostles. To that end, may we grasp precisely what they meant to say, taking each word in its real and authentic sense. For we are about to say what they already have declared as part of the mystery of revelation: that you are the eternal God, the Father of the eternal, only-begotten God; that you are one and not born from another; and that the Lord Jesus is also one, born of you from all eternity. We must not proclaim a change in truth regarding the number of gods. We must not deny that he is begotten of you who are the one God; nor must we assert that he is other than the true God, born of you who are truly God the Father.

Impart to us, then, the meaning of the words of Scripture and the light to understand it, with reverence for the doctrine and confidence in its truth. Grant that we may express what we believe. Through the prophets and apostles we know about you, the one God the Father, and the one Lord Jesus Christ. May we have the grace, in the face of heretics who deny you, to honor you as God, who is not alone, and to proclaim this as truth.

This prayer is an excerpt from a sermon On the Trinity (Lib 1, 37-38: PL 10, 48-49) by Saint Hilary of Poitiers.